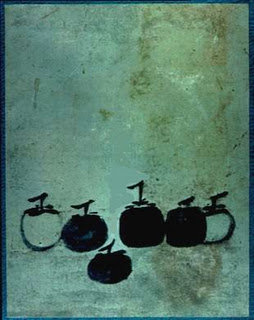

When I last wrote about painting persimmons with Stacey Vetter, a number of people asked me to keep them "posted." I had the best of intentions but my production took a sharp downturn high up in the hills of Carmel Valley.

While my son Ben played golf on the tiered greens of Saint Lucia Preserve, I hid myself behind a Valley Oak and began to paint acorns and oak leaves. The sun was hot and rather than creating distinct layers, the walnut ink pooled on paper. After an hour, I had only a few clusters to show for my efforts. Discouraged, I decided to report my findings to Stacey the next week.

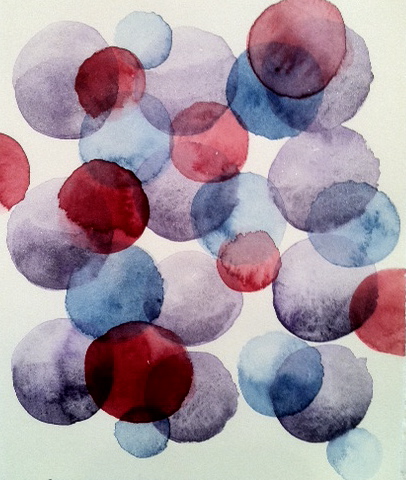

Stacey took a survey of my results and prescribed painting circles. "Circles??" I asked. Not one to stand on ceremony, she picked up her brush and began to demonstrate what she meant. As I watched her, I noticed that she handled the brush with a deftness born of deep practice. The brush seemed to swirl around with no hesitation.

I took up my brush, discovering that it intended design on its own--and performed the opposite of hers. Frustrated, I reminded myself of the revered book by Shunryu Suzuki: "Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind." "It's O.K." I assured myself. I have to work against my own grain when I put myself in a place where I know very little and I need to have a high tolerance for mistakes.

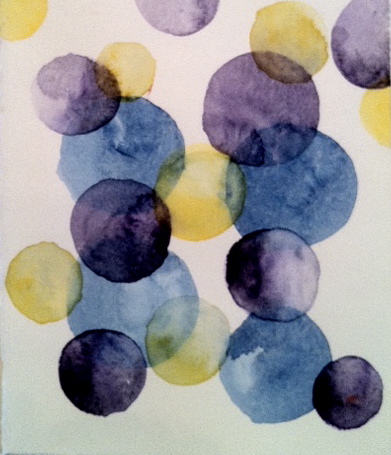

I decided to persevere. As I did, I began to notice little things: how as I came around the bend of the curve and the brush seemed to be running out of ink, it would disperse just enough ink to easily close the circle. Slowly, as I repeated the circles, I began to feel the delight I experienced as a child on ice skates when I figured out how to spin. Soon I was spinning the ink. Circles and more circles. On hot press. On cold press. On rice paper. On banana paper.

My next challenge was to create a shading in the circle. Stacey explained that I would need to paint a piece of the circle and then stop; making sure to leave an organic shape, quickly rinse my brush and then, with precisely the amount of water as I had just shed of pigment, finish off the circle.

A few days later at a studio time with my friend Linda, a landscape water colorist, I decided to try my hand at it. She sat down to complete a gorgeous landscape of Lake Tahoe and I brought out my circles. She glanced over after a while and noted that how boring it must be. Her comment caught me by surprise. I had become completely involved in the act of touching paint to paper and watching it react.

In its own way, it was as fascinating as observing a patient in her hospital room. How did the first stroke lay down? (Is the patient alone in her room?) What kind of organic shape should I leave? (What kind of expression does the patient have? What is the tone of their speech?) Does the paint granulate as it begins to dry? Is it a staining or non staining pigment? (Does she want to cover the entire paper or work in just a tiny corner?)

Like the beginning of William Blake's poem, "Auguries of Innocence," it seemed that I'd discovered "a world in a grain of sand."

To see a world in a grain of sand, And a heaven in a wild flower, Hold infinity in the palm of your hand And eternity in an hour.

After I explained to Linda what I was seeing, she too got caught up and soon we were both exploring the depths of her vast collection of colors. They were seductive, those circles, and she couldn't resist trying her hand at a few.

I'm not sure where these circles will lead and I'm sure a few of them will land in collage works. In the meantime, I'm taking time to relish the turn of the brush.